For nurses at MU Health Care, March 2020 is the dividing line between what their job was and what their job became. COVID-19 altered duties, changed protocols and made an already demanding profession tougher.

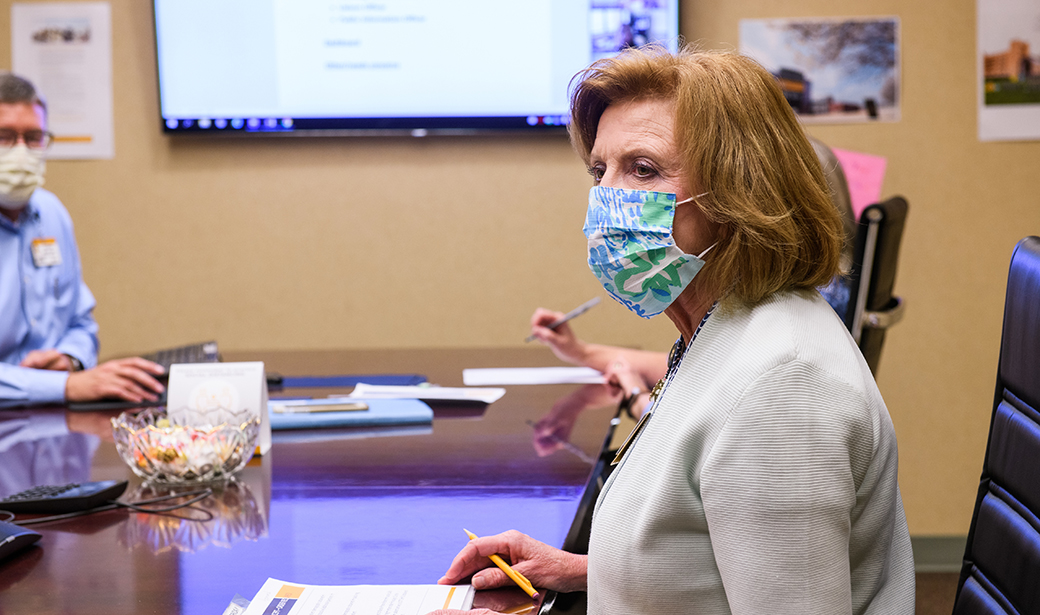

“I’ve been a nurse 44 years, and this was been the most challenging situation I’ve experienced in my career,” said Mary Beck, DNP, RN, who served as chief nursing officer at MU Health Care until her retirement in August 2021.

The greatest challenge was met with innovation, preparation and compassion. Here are the stories of four nurses — all of them graduates of MU’s Sinclair School of Nursing — who have played key roles in MU Health Care’s pandemic response, from administrative planning, to testing, to vaccinations, to direct patient care.

Incident commander

On March 12, 2020, MU Health Care established a COVID-19 incident command. Beck and chief medical officer Steve Whitt, MD, were selected as co-incident commanders.

“Mary was the perfect person to lead this, along with Steve Whitt, and I knew that from the beginning,” MU Health Care CEO Jonathan Curtright said. “She is an amazing leader. There was no other person I could think of that would be better.”

Beck and Whitt faced a challenge of staggering complexity. The task required essentially setting up a hospital within a hospital by establishing isolated areas to test, admit and care for patients with COVID-19 while still providing necessary health care to uninfected patients. They had to make these plans in an environment in which little was known about how the virus was transmitted, how hard it would strike Missouri or whether the health system’s supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) would be restocked regularly.

And they needed to get the job done in a hurry.

The incident command team, which also included section chiefs in charge of specific areas, initially met twice a day, at 8 a.m. and 4 p.m. It quickly transformed MU Health Care into an academic health system capable of handling a pandemic.

“The first month was really intense, creating our COVID-19 response plan, using the framework we already had with our pandemic plan but constantly adding details,” Beck said. “As incident commander, Dr. Whitt or I led every meeting. The section chiefs would bring information in that they had been working on the last eight hours, like, ‘How are we going to manage distribution of personal protective equipment during this pandemic with supply chain disruption?’ We would discuss and make decisions.”

Beck and the incident command team used a tiered response system that dictated policies based on the total number of COVID-19 positive cases and inpatients. At first, elective surgeries and procedures were postponed to free up beds and preserve PPE for a potential surge of COVID cases. Almost overnight, doctors who had never used telehealth were treating all their patients through the Zoom video-conferencing platform.

The next challenge was creating a safe path for a return to elective surgeries and procedures, with new safety measures like plexiglass and distanced chairs in waiting rooms. Beck said she has been inspired by the resilience of the employees she leads.

“What’s most rewarding to me is the way the staff of MU Health Care pulled together and said, ‘We’re going to do our very best work and continue to provide excellent care to all who seek to come here,’ even when they’re being challenged on a personal level,” Beck said. “We’ve problem-solved together and supported each other.”

Going mobile

Beginning in March 2020, Jeanette Linebaugh, RN, was not just MU Health Care’s senior director of nursing for ambulatory care services, she was also the manager of the drive-thru testing site located next to the MU softball stadium.

Without much to go on regarding staffing, workflow, patient volume or how to set up the necessary IT equipment in a parking lot, Linebaugh led the team that created the testing site from scratch.

It took just two days.

“In nursing school, we were taught to think through workflows and what they looked like from a patient perspective and from a staff perspective,” Linebaugh said. “I drew on my abilities to critically think and be innovative on how to serve the community.”

For the first six weeks, Linebaugh was on location every day. A revolving cast of 10 to 12 medical assistants, patient service representatives, nurses and many other health care professionals worked at the site each day. After a few months, they grew close and even began appreciating the charms of their new home, which consisted of an emergency trailer and an expanse of asphalt.

“COVID is scary to people, so they were thankful we were out there in the elements taking care of them,” Linebaugh said. “Also, from the staff that was working there, so many said, ‘I love doing this for our patients and the community.’ ”

Because of increased patient volume — as many as 700 people were tested in one day —Linebaugh again took a leadership role. She helped organize the high-throughput vaccine site at Faurot Field that was able to give thousands of shots per day to the public.

“Serving the community during the pandemic has been one of the most humbling experiences in my nursing career,” Linebaugh said. “When members of the community enter the doors of the Columns Club at Faurot Field, I see hope in their eyes — hope for a better tomorrow, a tomorrow where they can see their grandchildren, friends and loved ones without fear of getting sick.”

(The Faurot Field vaccination site closed in June, and vaccinations are now available in select clinics and pharmacies. Learn more.)

Together at a distance

By design, MU Health Care’s psychiatric patients are brought together frequently. They eat together, go to group therapy sessions and interact with each other in the evening over card games and board games.

So when the COVID threat reached Missouri, Debra Deeken, DNP, RN, the executive director of clinical operations and director of nursing for the Missouri Psychiatric Center, knew she and her fellow department leaders would have to change familiar ways. They began writing down the necessary changes, and it grew into a document that is “many pages long” as MU Health Care’s infection control team and the Centers for Disease Control learned more about the virus.

“We looked at every single process we had and had to think through ways to mitigate infection risks in everything we do,” Deeken said. “For example, we had to pull chairs out of our unit so our patients could be six feet apart where they eat and where they sit in the TV lounge. We had to put practices into place where we cleaned every single horizontal space on the unit, including doorknobs and push plates for doors, every hour. There was an incredible amount of effort put into place to keep our patients and staff safe from COVID-19.”

Deeken gained a new appreciation for the importance of over-communicating with her nurses and staff, not just about all the changing procedures they needed to follow, but also about their personal stress and struggles.

“My clinical knowledge and leadership education help me work through processes, pull people together, initiate change and follow through on that change,” Deeken said.

Compassion in the MICU

TJ Headley, RN, has worked in University Hospital’s medical intensive care unit since graduating from nursing school in 2018. He’s used to serving the sickest patients, but the job had a new twist during the pandemic — connecting patients with the loved ones who couldn’t visit them.

“That’s hard on the patient and hard on the family members,” Headley said. “We’ve done our best to make sure they can see their loved one, even if it’s through Zoom on an iPad, and to see we’re caring for them and doing everything we can. Some nurses will take care of a patient for two or three weeks in a row. They’re sick for a very long time, and family members call every night, and we kind of get to know them.”

One of Headley’s most rewarding nursing experiences came early in the pandemic. He was working in the COVID unit and admitted a new patient. They got to know each other, and Headley did his best to calm the man’s nerves.

“The next night I came back to work, and he was already on the ventilator,” Headley said. “That was tough. But within a couple weeks, he got off the ventilator, actually went out of the ICU and got to go home. A family member came back and had hand-written thank you cards for everyone that had taken care of him. That is probably the most rewarding thing, getting to see patients be at their very worst and then come out of it and get to go home, back to their families.”

Published July 19, 2021