Norm Stewart knows how to build a team.

A man who needs no introduction in the state of Missouri, and in many places outside it, the Shelbyville, Missouri, native had an eye for talent that helped win a lot of basketball games.

Above all else, he made a positive impact on generations of Missourians: his players, their families, the legions of Tiger faithful who packed the Hearnes Center to cheer on his program. They all saw first-hand the things you can accomplish with great teamwork.

But in September of 2021, he needed a different kind of teamwork to help him beat an adversary more relentless than any Jayhawk, Wildcat, Cyclone or Sooner.

Following a routine hip replacement surgery, Stewart developed two open wounds on his left leg, one above his heel and one on the outside of his ankle. Despite everything his doctors tried, the wounds refused to heal and destroyed his exposed Achilles tendon. Stewart was told his leg might need to be amputated.

“I was in a position where I could have had something serious happen, such as the loss of my foot, my leg or my life,” Stewart said. “One of my friends said, ‘Norm, you’ve got a serious problem.’ Thank goodness I was directed to Dr. Nuelle and Dr. Stannard.”

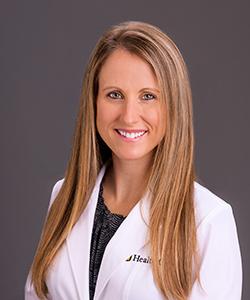

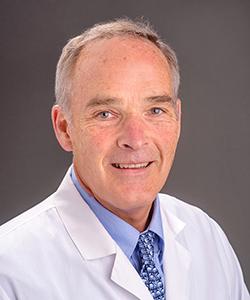

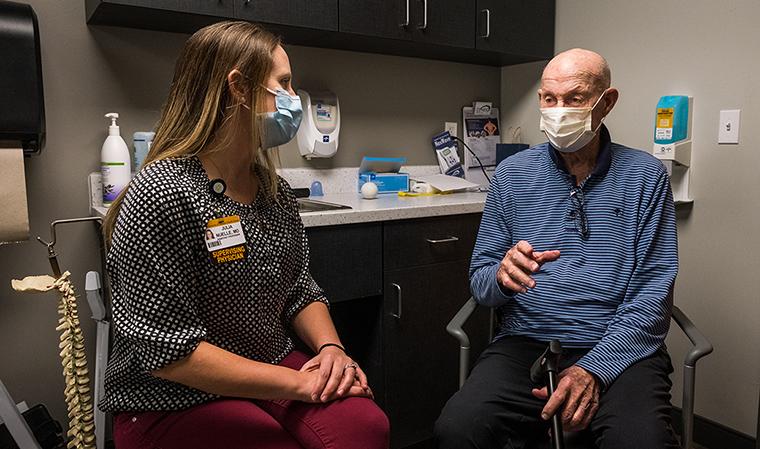

Stewart was encouraged to get a second opinion at MU Health Care’s Missouri Orthopaedic Institute, where he was introduced to the people who would become captains of his treatment team: Julia Nuelle, MD, a microvascular surgeon, and James Stannard, MD, an orthopaedic surgeon who specializes in infection and trauma.

When Stewart met with Drs. Stannard and Nuelle, they couldn’t promise his left leg was safe. But they promised they’d try to save it.

“For someone in his age group, being able to keep the leg is crucial,” Nuelle said. “If you think about having to put on a prosthetic in the middle of the night if you're getting up, or even in the morning getting up as part of your routine, it can be very challenging. Saving a limb is life-changing.”

Although Stewart’s leg wounds weren’t healing, he had good blood flow to the site and was in excellent physical condition. Those factors gave his team hope amputation wasn’t the only option. But there was still the necrotic (dead) skin and muscle in shades of purple and black on Stewart’s leg to deal with, and his visible discomfort moving because of the wounds.

“I told him at that first visit it didn’t look good. It didn’t smell good,” Stannard said. “I was concerned it was infected and had necrotic tissue, but I couldn’t get a handle on it without going into the operating room.”

Both Nuelle and Stannard knew of Stewart and his reputation: tough but not mean, commanding a presence without being loud, measured in his words and actions. If he was afraid of losing his leg, Stewart went into the unknown of Stannard’s first procedure without showing it.

"You learn not to react too much,” Stewart said. “And that's just my personality, anyway, is to get the news and then kind of go through it. But it was a relief, to say the least, to hear, ‘Okay, everything is going to be all right. It's just going to take some time.’”

Like all limb preservations at the Missouri Orthopaedic Institute, Stewart’s treatment team had even more depth than a basketball roster. Surgeons, pre-operation nurses, OR nurses, anesthesiologists and post-anesthesia care unit nurses, limb preservation coordinators, social workers, home care workers and physical therapists all played their role.

“Sometimes we don’t realize how lucky we are, having one facility dedicated to the skeletal system,” Stannard said. “We have subspecialty nurses, a phenomenal OR team, trauma people, sports people. We have all these pieces we can pull together, and all together it makes a huge difference.”

Stannard performed at least two surgical debridements, or procedures to clean the wound, cutting out dead tissue and flushing the wound with liters of sterile fluid. In between the surgeries, Stewart’s body would heal what it could, reveal what it couldn’t, and Stannard would make another pass.

Once the wound was clean, Nuelle stepped in. She performed a peroneus brevis flap surgery for the larger wound, cutting muscle from his calf above the site and laying it overtop the part of his leg that wouldn’t heal. It’s a tricky task: Nuelle has special training to delicately connect tiny blood vessels together, making sure the tissue is kept alive with blood flow.

The smaller wound on his ankle healed with a specialized mesh patch, resembling chicken wire, that makes the body’s natural recovery processes easier. Dr. Nuelle also performed skin grafts from higher up Stewart’s leg, sewing the skin over his wounds to protect them.

The team’s effort was a success: they had saved Norm’s leg.

“I wish they all would've played for me because I think we would've won a lot of games,” Stewart said. “I tell everybody Dr. Nuelle is really remarkable. Her skills and bedside manner, she's a person that cares. She is just an excellent craftsman.”

Although Stewart is still recovering with physical therapy, he and his wife Virginia were happy Norm's leg was strong enough to attend the 15th annual Norm Stewart Classic high school basketball shootout at Mizzou Arena in December.

He’s slowed a little, now attending about 15 games a year instead of the 30 or so in years past. But he loves the game of basketball too much to stay away: the people, the energy and everything that comes with being part of a team.

After all, that’s what he knows best.

“I think a key to any team is that you have multiple different players who each fill a special role,” Nuelle said. “That's really what we have here. Being able to demonstrate that to Coach, who's been a leader of outstanding teams over the years, and for him to see that in us was an invaluable experience.”