A week after having a loop recorder implanted to monitor her heart rhythm, Mary Andersen was at home reading a magazine when the phone rang. The call was from University Hospital. Her recorder had alerted the cardiology clinic that Andersen’s heart was racing.

“The person asked, ‘What are you doing?’ ” Andersen recalled. “I said, ‘I’m reading.’ I hadn’t done anything to trigger it. It really started going crazy.”

Andersen was suffering from a condition called atrial fibrillation — a rapid and irregular heart beat originating in the upper chambers of the heart. Her racing heartbeat during a calm moment without any other known triggers such as alcohol or caffeine consumption was a sign that medication alone wasn’t working to solve her problem.

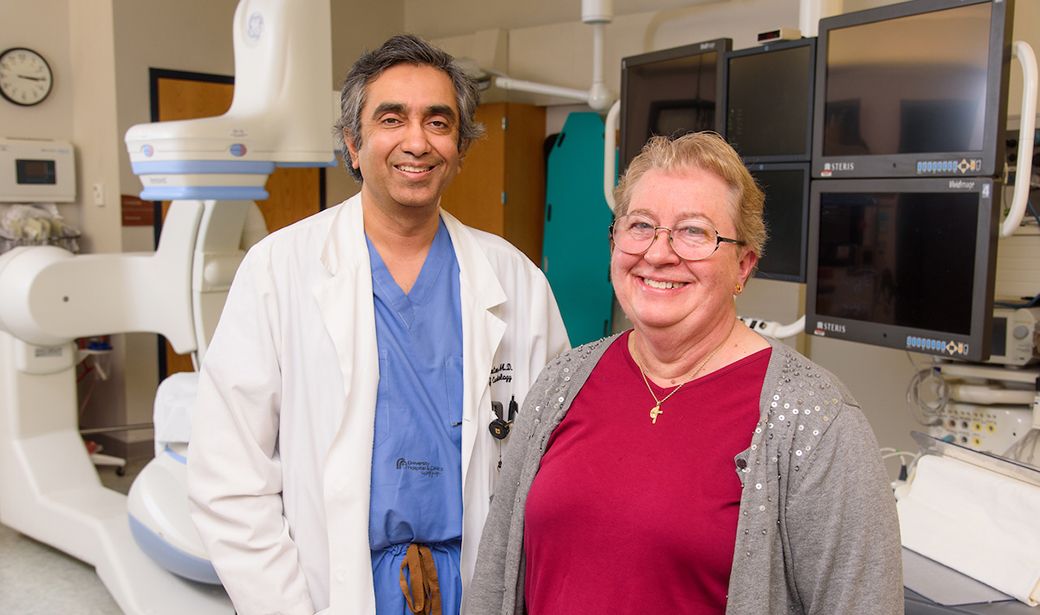

A few days after that phone call, MU Health Care's Sandeep Gautam, MD, performed catheter-based ablation surgery. Since that procedure in October 2015, Andersen has experienced only one AFib episode, and that was when she was ill after drinking sour milk.

“Atrial fibrillation is getting more common as our population is aging, especially because baby boomers are in their 70s now,” Gautam said. “A big influx of atrial fibrillation is coming up. You can imagine the degree of atrial fibrillation incidence by the fact that atrial fibrillation ablation is now the most common ablation procedure performed for any kind of rhythm problem. If you go back 20 years, atrial fibrillation ablation was 20 percent of the procedures we offered. Now it’s almost 75 percent.

“So it’s extremely common. If you go to any local nursing home or long-term residential area for the elderly, you’ll find at least 25 percent of them taking some medicine for atrial fibrillation.”

Andersen, who worked as a research specialist in the MU School of Medicine’s Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Environmental Medicine until her retirement in 2015, was diagnosed with AFib in 2011.

“It feels like a really sharp pain in your chest,” she said. “You can feel your heart is beating really fast. It’s just kind of throbbing. Then you start to feel generally bad, like when you’re getting really sick. You don’t want to do anything or exert yourself in any way.”

Patients who experience those symptoms should contact their primary care physician or cardiologist. AFib causes blood to pool in the heart, increasing the possibility of stroke. AFib risk factors include a family history of the disease, uncontrolled high blood pressure, uncontrolled diabetes, obesity and untreated sleep apnea.

After diagnosis, the first step is for a patient to receive an electrocardiogram and wear an outpatient heart monitor for one to 30 days. A shock to the heart called a cardioversion in conjunction with anti-arrhythmic medication can sometimes restore the heart to its normal rhythm.

Ablation procedures often can fix the problem and allow the patient to get off anti-arrhythmic medications.

“We use a technique called radio-frequency ablation, which uses radio-frequency energy to create what you can imagine as very low-power welding inside the heart,” Gautam said.

The procedure takes three to five hours. A catheter is inserted in the groin and run through the femoral vein to the heart. A puncture is made in the wall separating the right and left side of the heart. The source of AFib in most patients is the pulmonary veins in the left atrium of the heart, so a set of lesions is created to disconnect the electricity to those veins. The patient is usually monitored for a day and then released from the hospital.

Andersen has made some minor dietary adjustments and now uses a CPAP machine for her sleep apnea to guard against triggering her AFib. Otherwise, it’s business as usual for Andersen, an avid reader who enjoys volunteering in the library at Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church.

“She is off medicine for atrial fibrillation,” Gautam said. “She had an excellent response with great clinical improvement.”